Project

Amsterdam Living Lab

During the Amsterdam Living Lab, 100 residents of Amsterdam actively contribute to research on the indoor climate. Each living lab of the wider EU project I-CHANGE has a focus on a climate issue. In cooperation with the AMS Institute and Wageningen University & Research (WUR), Amsterdam is looking at heat, and through citizen science at the indoor climate.

Within WUR's departments, much research has already been done on urban heat, but little was known about the indoor climate. People that are weaker are especially affected by heat. If it does not cool down in the evening, they cannot recover. Residents of Amsterdam shared many own experiences with heat during the project and it turns out that it is a bigger problem than originally expected. For example, for one resident outdoor temperatures of 26 degrees meant that it could heat up to 42 degrees at his home. The main aim of the project is to bring attention to this indoor climate. At the start of the project, many residents talked among themselves about the problem and through this snowball effect, 100 people eventually gathered who wanted to participate in the study. As part of I-CHANGE, the Living Lab was initiated in Amsterdam.

Weather stations were placed in participants' living rooms and bedrooms. The weather stations measure not only temperature, but also humidity and CO2 concentration. The data is used for the study, but the participants themselves also get access to the data in an app. This raises awareness about heat in the home and provides understanding of when people can ventilate (open the window). Ventilation is necessary not only to regulate temperature. One of the participants, a father, realised that at night CO2 levels were getting too high in his child's room. They now always keep the window ajar.

Results

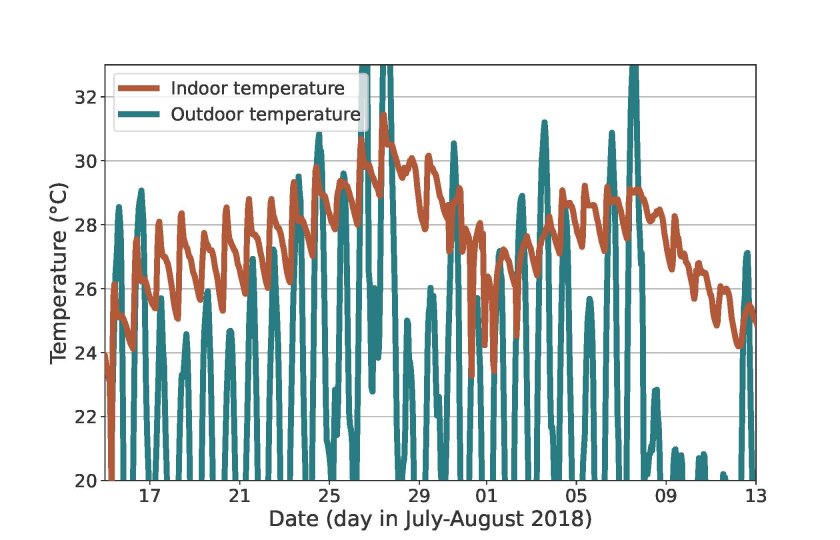

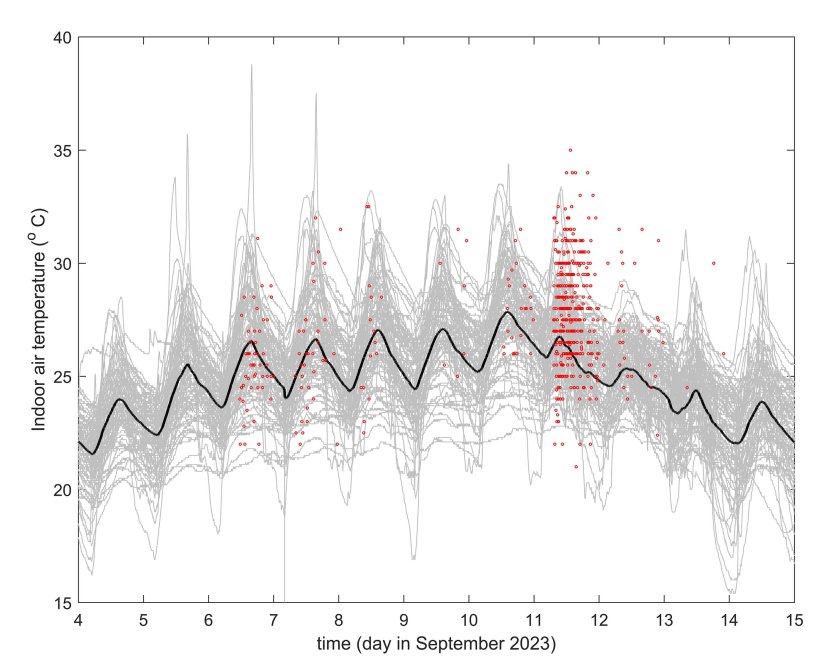

The researchers soon realised that the difference in temperature between indoors and outdoors was greater than expected. The network of 24 weather stations that was already present in Amsterdam's outdoor space facilitated the researchers' ability to compare the data with outdoor temperatures. With climate change, urban heat island effect and high indoor temperatures, heat is a tricky problem in the city. Especially for people who are indoors and find it difficult to sleep at night due to the heat. Data from indoor weather stations can be used to demonstrate the huge delay in cooling indoors. When it starts cooling down outside, it heats up inside the house for another 4 hours due to the thermal mass of the building. In addition, if there has been a heat wave, the heat indoors stays for another 5 days (see also Figure 1). This could mean that heat plans, from RIVM and others, would have to stay in action for 5 more days. Health risks increase once the heat increases, and sleep problems arise. During the September 2023 heatwave, through a citizen science event, 570 residents of Amsterdam reported their temperature. Although the health threshold in temperature is 24 degrees, almost all values from these measurements were above (Figure 2). Radiation from the sun through a window affects this indoor temperature most, even more than the outdoor temperature during summer.

Besides these results, the project has also generated a lot of awareness about the problem. For example, the researchers send a newsletter to participants to keep them informed about the progress of the study. This newsletter generates a lot of interaction and interest, demonstrating that the problem is close to the people themselves. In addition, more attention is drawn to the problem through news articles, radio broadcasts and workshops. This creates more awareness among vulnerable groups and policymakers. Also in Wageningen, the researchers contribute to the course Urban Hydrometeorology to further disseminate knowledge on the topic. The researchers found that communication is crucial to the success of a citizen science project. Although many people get and stay involved, this only happens effectively if it is communicated well.

Next steps

Next steps within the project build on the Living Lab and contribute to further understanding the factors that influence indoor temperature dynamics. For instance, a model is now being developed that incorporates the climatology of the houses in predicting indoor temperatures. The 100 occupants provide information on building design (e.g. room area, orientation and window area, energy label), about human behaviour (how do they experience heat in their home and what do they do about it (e.g. when to ventilate and do/do not close curtains)), and about the environment (e.g. local climate zone). The researchers will look at whether relationships exist between these factors and indoor climate. Some Bachelor and Master students from Wageningen University also add to this research during their thesis.

In short, citizen science plays an important role in the insights surrounding the indoor climate in Amsterdam. This may ultimately lead to empowering the Amsterdam community and raising awareness for the problem of indoor heat.