category_news

Professor Sander Koenraadt: “We must prevent mosquito havens”

If we wish to avoid being overrun by mosquitoes in warm weather, we must intelligently design our surroundings. This is one of the key messages from researcher Sander Koenraadt in his inaugural lecture “Blood, sweat, and fears” on 21 March, as he is appointed Personal Professor in Ecology and Control of Disease-Transmitting Vectors at the Wageningen University & Research (WUR) Laboratory of Entomology. Koenraadt explains what can be done to combat these buzzing insects, which - due to climate change and pesticide resistance - pose an increasing threat to both humans and animals.

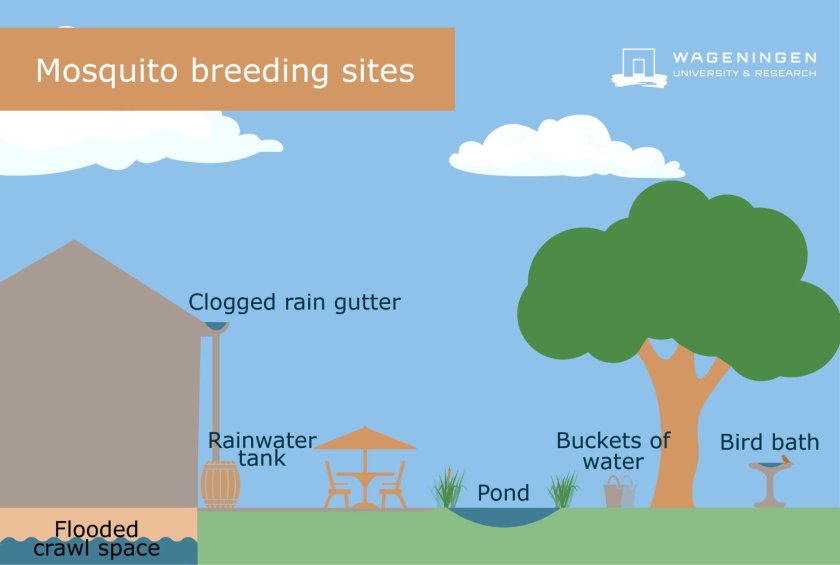

Now that the warmer days are upon us, mosquitoes are set to appear more frequently - especially in our bedrooms. “It is inevitable that we will encounter them again,” explains Koenraadt. “But we can ensure that their populations remain limited. For instance, by avoiding the creation of mosquito havens in our local environment. Don’t leave buckets of water in your garden on warm days and refresh the water in bird baths on a weekly basis. While an increase in urban green infrastructure is vital for our health and for climate adaptation, we mustn’t overlook that it can also provide breeding sites for mosquitoes.”

The rise of invasive species

Although a sleepless night caused by the constant buzz or a few itchy bites is annoying, the true danger of mosquitoes lies in their role as disease vectors. Species capable of transmitting diseases are steadily moving into Western Europe, driven by climate change. “A good example is the tiger mosquito, which can spread viruses such as dengue and chikungunya. Milder winters make it easier for mosquitoes to survive here throughout the year. These insects can easily arrive from Southern Europe - for example, in a camper from Italy,” Koenraadt points out. “Furthermore, we know that the common house mosquito - the most prevalent species in the Netherlands - can transmit the West Nile virus. In 2020, this virus was detected in our country for the first time, and since then, several cases of encephalitis caused by the virus have been reported.”

Determinants of disease transmission

As a researcher, Koenraadt takes a broad interest in vectors - blood-sucking creatures that transmit bacteria, parasites, or viruses to humans and animals via their bites. “In addition to mosquitoes, this group includes ticks and flies, such as the tsetse fly and sandfly. A key question is which conditions determine the transmission of pathogens. We are investigating, among other factors, the roles that ecology, pesticides, and climate change play. For example, how do higher temperatures accelerate the spread of diseases? And why does one mosquito species carry one pathogen while another species carries a different one?”

The global impact of mosquitoes

His research does not focus solely on the risks of emerging diseases in Western Europe but also on the worldwide dangers posed by mosquitoes. “Countries in the Global South, in particular, suffer enormously from disease-carrying mosquitoes, with malaria being the greatest threat. In fact, malaria-transmitting mosquitoes are the deadliest animals on the planet. Infections have a massive impact on communities and families - not only in fatal cases. Sick children may miss school, and adults might be unable to work or care for their families. Often, people are infected several times a year.”

Interdisciplinary collaboration

Interdisciplinary collaboration is central to Koenraadt’s work as a Personal Professor, he says. “For instance, within the field of Entomology we conduct extensive laboratory research together with the Virology department on the behaviour of a mosquito once it becomes infected. Does the mosquito itself suffer as a result? Our collaboration with virology has been long established. Based on earlier research findings, we predicted ten years ago that the West Nile virus would make its way into Western Europe - and that has now come to pass. We also work closely with modellers, who help us to understand how the interaction between viruses and mosquitoes changes with temperature.”

The role of social science

Another important discipline is social science. When combating infectious diseases, human behaviour also plays a role - for example, in taking preventive measures. One of the research projects involving social scientists is taking place in Rwanda. “Here we have set up a programme for the biological control of malaria mosquitoes in rice fields. These irrigated fields are significant breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Rather than spraying pesticides, we use a bacterial spray that kills the larvae of malaria mosquitoes. This approach has proven incredibly successful, although it naturally takes time to demonstrate its effectiveness and to convince farmers that it is a better option than pesticides.”

Releasing sterile males

Biological control is not only important for the health of people and the environment, but also because mosquitoes are becoming increasingly resistant to pesticides, Koenraadt continues. “In such cases, those chemicals are completely ineffective. In addition to a bacterial formulation, one could consider more drastic biological solutions, such as releasing sterile males. In this process, male mosquitoes are treated in the laboratory with a bacterium and then released into the wild to mate with females. Since this mating leads to sterility, the overall mosquito population declines. This method is already being experimented with in countries like China, Brazil, Italy, and Indonesia - often with success. It is something that could also be considered in the Netherlands.”

Inspiring the next generation

Koenraadt hopes to inspire students in the coming years just as his predecessor, Willem Takken, did. “Through his lectures, I truly came to realise the enormous impact these tiny creatures can have on both people and animals, particularly when they spread diseases. I found it so fascinating that I wrote my master’s thesis on the behaviour of biting mosquitoes and then pursued doctoral research on malaria. There are more than 3,500 mosquito species, each with its own unique characteristics. There is still so much to discover - we have barely scratched the surface. Given the growing global population and climate change, this field is only set to become even more interesting and important.”